The self and the structure of the personality — IX

Matthijs Cornelissen

last revision: 02 November 2025

locating the centre and the borders of the self

Introduction

The centre and the borders of the self are perpetually shifting and in a person’s ordinary waking consciousness, our sense of who we are can include not only our body, mind, and personality, but even possessions, other people, roles, group-memberships and whatever else we happen to identify with at a given moment. What we consider our self and where we locate our borders, can vary over a stunningly vast range. To make things more complicated, we tend to have, simultaneously, different identities on different levels. There is a deep identity that hardly changes, if at all: you are, at least in some strange way, the same person you were when you were one year old, or even younger. There are other identities which change slowly, over long periods, like those related to your work, social position, close family, health, country, faith. And finally, there is a surface identity which cheerfully flips from one state to another in a fraction of a second, as when you are engrossed in a book, and a sudden sound or physical touch makes the centre of your identity jump almost instantaneously from some imaginary reality in the mind towards the body.

Four ways to conceptualise the centre and the borders of the self

Interestingly, the average and the ideal location for the borders of the self differ not only between individuals but also between different knowledge systems and (sub)cultures. The table in this section intends to give a quick, schematic overview of four different ways of conceptualising the self.

- The divisions on the horizontal axis of this table are based on a concentric view of our subjective reality: On the left is our deepest, innermost essence. It is the secret uppercase Self all spiritual traditions urge us to discover. On the right is our outermost physical environment. We have divided the area in between into three: on the left our individual essence, our Soul; in the middle our body (our "skin-encapsulated" individual being); and on the right our social environment.

What we feel as our self, what we subjectively are and identify with, tends to centre in our physical body but stretches to the left and right. - Vertically we have listed four typical ways of thinking about the self. The first is that of mainstream, academic psychology. The second is the largely implicit, home-grown folk psychology that many "ordinary" people tend to live by. The third is the ideal put forward by what we have called "exclusive spirituality". The last is the integral psychology presented in this text.

Table 11b-2. The border between Self and World

There are obvious limitations to such an overly simplistic, two-dimensional diagram. We are all different and while for most people their human relationships may be closer to themselves than physical things, there may be exceptions. For a devoted carpenter, for example, the wooden furniture he is working on may actually be nearer and dearer to his self than his immediate family. So for him, while he is working, the column indicating his physical reality should actually be to the left of the column indicating his social reality. What is more, the demarcations between different knowledge systems and aspects of reality are not as sharp as they are in this diagram. Even when groups are quite different from each other as a group, the individuals within those groups can still have every possible opinion and every possible characteristic. This is especially true when the groups are large and have existed over a long period of time. So, as long as we keep in mind that this diagram indicates at best some general tendencies and centres of gravity, we could then say the following:

- Mainstream American psychology is based on a worldview that takes the physical world as the primary reality. It assumes that all mental activities have a physical origin in our biochemistry and nervous system, and so it considers character, personality, traits and dispositions to be part of ourselves, while work, relationships, group-membership, other people and possessions etc are seen as belonging to the "outside" world. It has no place for the soul or for pure consciousness. In short, its concept of the individual is strongly "skin-encapsulated".

- Most folk psychologies don't have much to say about pure consciousness either, but "ordinary people", even in Europe and the USA tend to believe in the soul and life after death. The details of how people think about these things differ, however, considerably from culture to culture. Folk psychologies may differ even more regarding the relation between individuals and their social environment. In India, for example, the concept of family includes more distant relatives and is more hierarchically structured than the concept of family in Europe and the USA. Still, the differences between cultures are not that large and one could probably say that in almost all folk-psychologies the borders of the self tend to extend further towards the spiritual and further towards the social than in the scientific view.

In the philosophical and spiritual traditions of India, the situation is again quite different. Here the essential identity of the individual tends to be seen as a centre of pure consciousness, and not as an egoïc, social or physical organism at all. In other words, most spiritual traditions in India place the ideal borders of the self radically further inside, so much so, that the centre of identification becomes one with the Transcendent or, as in some forms of Buddhism, disappears altogether. In this table, we have distinguished two types of Indian spirituality, one exclusive, one integral.

- The exclusive schools all advocate realization of the Transcendent as the ultimate goal, but they differ in how they look at the individual soul and the manifest world. The mayavadin interpretation of Advaita Vedanta considers both individual differences and the manifest world as illusions created by ignorance. Samkhya accepts the manifest world not only as real, but even as eternal, but considers it inferior to the Transcendent. In Buddhism the manifest world is considered real but characterised by suffering and in most Theravadin and some Mahayana schools, the individualised self is seen as lacking substance. In spite of their differences, in all these schools, release into a Transcendent nirvana is seen as our ultimate destiny. In the table, we have indicated the Transcendent with "That" (as the English translation of the Sanskrit tat) and everything else, when seen as unreal or irrelevant, with " - " .

- Integral spirituality accepts the value of realising the Absolute Transcendence, but also asserts that consciousness is power, and thus, that even one's eternal Self can have qualities. It excludes nothing as completely external or undivine, and strives for a state in which not only the formless Transcendent, but even the entire manifest reality is seen as part of ourself. As such there are then no real boundaries around the Self anymore: there is neither an unknown on the left, nor a non-self on the right.1

What is inside, what outside? What inner, what outer?

What we consider inner and outer depends on our vantage point. As long as we don't think too much about it (and keep psychology and philosophy at a safe distance) things are relatively simple: inside means inside a person (whatever that may mean) and outside means belonging to that person's environment. So, when we say, "his ideas come from inside", we mean that he has thought them out himself, and when we say, "his ideas come from outside", we mean that he may have got them from his friends or social media.

However, as soon as different kinds of philosophy and psychology get involved, the situation becomes quickly more complex. For the rest of this discussion, we will consider only two different viewpoints: the perspective of mainstream psychology as based on the ordinary waking consciousness, and the perspective of integral psychology as based on the puruṣa-centred witness consciousness.

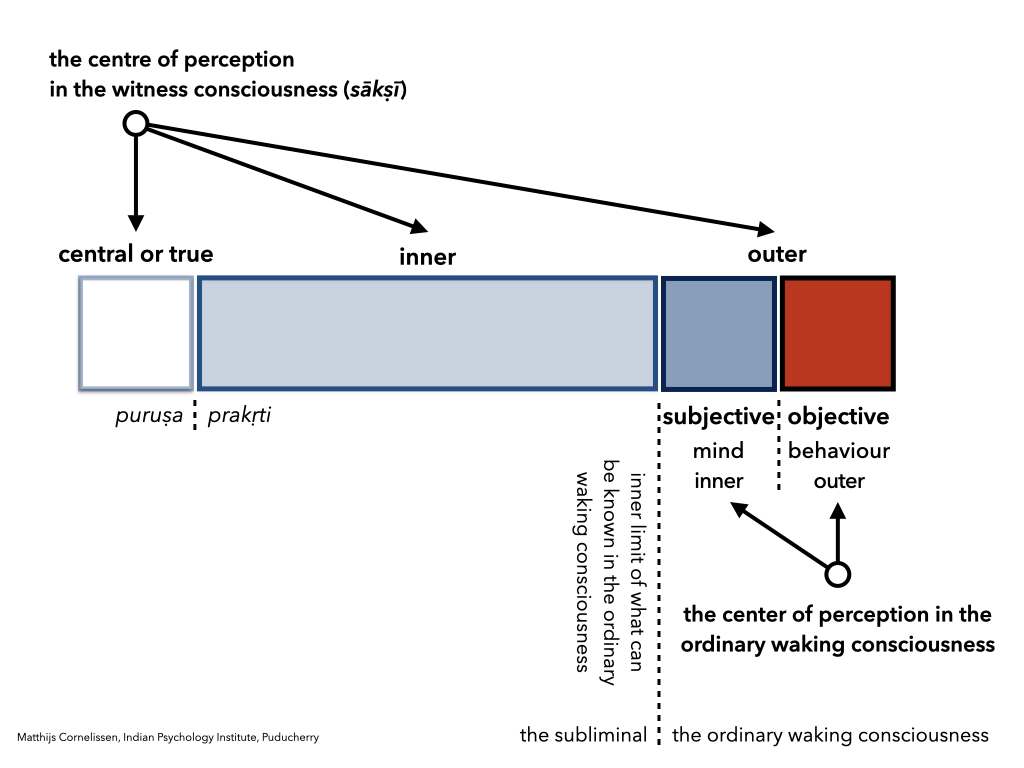

Figure 11b-4. Inner and outer: A shift of perspective

Mainstream psychology is limited to the ordinary waking consciousness. From its perspective:

- Our outer nature consists only of our objectively observable behaviour.2

- Whatever else is known about ourselves in the ordinary waking consciousness (which is very little) is called inner.

Integral psychology is based largely on the witness consciousness of the puruṣa. From its position, all that is known to someone in the ordinary waking consciousness is called outer, so:

- In its terminology, the outer nature contains not only one's behaviour but also all the feelings, thoughts, volitions and sensations that people are aware of in their ordinary waking consciousness.

- The term inner nature is here used only for those feelings, thoughts, volitions and sensations that people in their ordinary waking consciousness are normally not aware of. This much larger part of our nature is also called the subliminal, and occasionally the subconscient, though this latter term is also used more specifically for the lowest and darkest corner of the subliminal nature (the area which Freud called the unconscient).

- The last, innermost part is the Central or True being. It is our eternal (uppercase) Self or puruṣa. It is quite useful to distinguish this uppercase Self from the lower case self, which is the small part of the outer nature that the ego happens to identify with.

- Sri Aurobindo uses the term "inner being" quite often simply for everything that is not one's outer nature. It includes then what is here called "central or true".

How to study the inner and outer?

To conclude, a short note on how "inner" and "outer" fare in terms of the four knowledge realms [p. 113] discussed in the chapter "What is knowledge?":

- What mainstream psychology calls outer belongs to the realm of objective knowledge.

- What mainstream psychology calls inner belongs to the realm of subjective knowledge.

- What integral psychology calls inner belongs to the realm of inner knowledge.

- The innermost region containing the Soul and the Self belongs to the realm of knowledge by identity.

Endnotes

1One could say that as long as one identifies with a small and fragile biological creature in a big and threatening world one has to defend oneself, so one has to build solid walls around oneself. But if one identifies with one's eternal and immutable Self, there is no longer anything that needs to be defended or excluded. The reason there is suffering and imperfection in this otherwise(?) incredibly beautiful and well-made world, is that we have to develop into centres of conscious action that not only act in full harmony with the whole, but that are also as entirely free as the Divine is. To make such free yet perfect action possible, every last little crumb of our nature must be perfectly aligned with the whole of reality. While "enlightenment" can happen in a moment, this takes time and labour.![]()

2The manner in which the word "behaviour" is used in psychology, changed over time. In Classical Behaviourism, only non-verbal physical action was called "behaviour". Later, Cognitive Behaviourism added speech and writing as "cognitive behaviour". Throughout, behaviourist psychologists remained committed to being objective and did not study thoughts, feelings, volitions and sensations directly. Though they often discussed them as if they were real, they accepted as their raw data only their verbal descriptions (made by their subjects), non-verbal behaviour and physiological measurements. Accordingly, in Figure 11b-4 the word "behaviour" indicates only that part of us that is directly observable from the outside. .

To receive info on

Indian Psychology and the IPI website,

please enter your name, email, etc.