The ongoing evolution of consciousness — III

Matthijs Cornelissen

last revision: 08 November 2025

the necessity of an involution before the evolution

If you haven't read the previous two sections of

this chapter, you might like to read them first:

In the first section of this chapter, we looked from an Indian consciousness-centred perspective at the absolutely stunning evolution of life within matter and of mind within embodied life. In the second section we looked at what we called the post-biological evolution, the period in which there is a significant further evolution of consciousness within humanity. We will start this third section with a look at what might have happened before all this started: how the physical world has come into being. Or to say it more paradoxically: we'll try to figure out what happened "before" the Big Bang, if that makes sense given that with the Big Bang not only mass, energy and the laws of physics, but even space and time seem to have burst into existence. As we discussed earlier, the reason to start at the very beginning is that understanding our past may well give us a hint on what to expect next. So, from where did it all come?

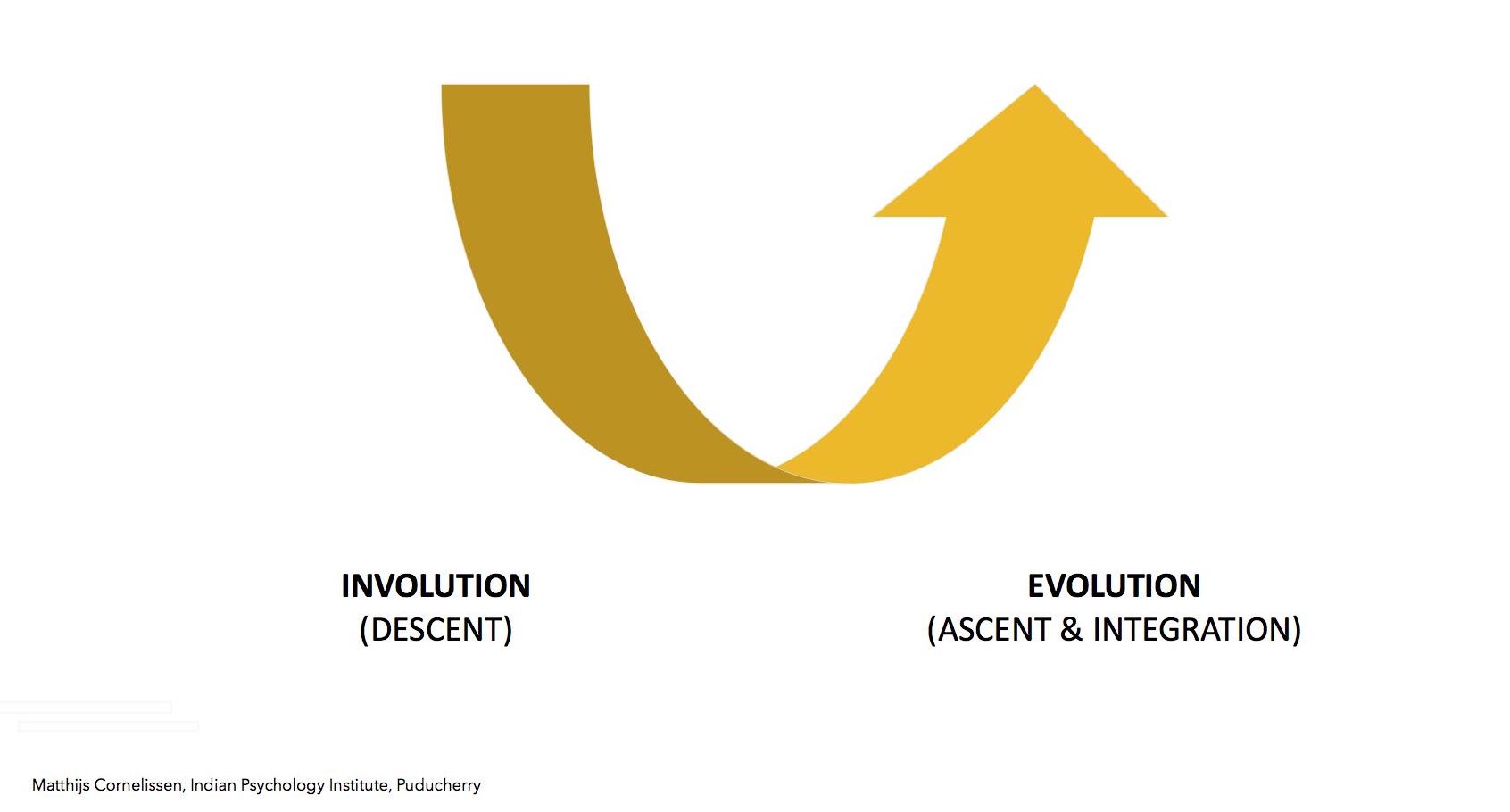

If we look at the biological evolution as a gradual emergence![]() of consciousness, that consciousness must have been hiding somewhere before it emerged. To use a perhaps over-simplistic metaphor, a magician cannot pull a rabbit out of a hat if he has not hidden that rabbit somewhere inside the hat before he starts. Similarly, consciousness cannot emerge out of matter if the basic principle of consciousness is not already there in some form or another. In other words, an involution of consciousness must have preceded the evolution, and this is exactly how the Indian tradition visualises the process that must have produced our present world. The combined process of involution

of consciousness, that consciousness must have been hiding somewhere before it emerged. To use a perhaps over-simplistic metaphor, a magician cannot pull a rabbit out of a hat if he has not hidden that rabbit somewhere inside the hat before he starts. Similarly, consciousness cannot emerge out of matter if the basic principle of consciousness is not already there in some form or another. In other words, an involution of consciousness must have preceded the evolution, and this is exactly how the Indian tradition visualises the process that must have produced our present world. The combined process of involution![]() and evolution can then be depicted as in Figure 1.

and evolution can then be depicted as in Figure 1.

Figure 07c-1. Involution and evolution

In case your next question is "But from where did saccidānanda come?", I don't have much to say. For me, personally, the idea that saccidānanda, a unity of being, consciousness, and joy, is eternal and will be there as long as it pleases itself to be there, is quite satisfactory (and definitely better than that it all started with a big bang).

As we saw earlier, the Indian tradition developed the concept of saccidānanda, a unity of true being, consciousness and joy as the nature of the ultimate reality. And since, according to integral Vedānta, the entire universe is a manifestation of that ultimate reality, saccidānanda should not only be the origin, but also the essence of everything in existence. In other words, everything in this universe must be conscious and joyful. At first sight, this may be hard to accept as there are plenty of things in this world that to us don't look conscious and joyful at all, but if we think about it a little deeper, we have to admit that this may be due to a too narrow, anthropocentric view of reality. The history of physics shows how helpful it can be to leave such anthropocentric perspectives behind. In ordinary life we measure temperature in Celsius and Fahrenheit, which both have positive as well as negative values because for us, as small biological creatures in a large and not always human-friendly environment, things can be too hot or too cold. But physicists have found it more helpful to measure temperature in Kelvin which has only positive values. This works for them because they understand temperature as the energy in things, and in their knowledge system nothing can exist that has zero energy. The Vedic concepts of Consciousness and Joy which we will use in this text are defined in a similarly professional manner. Just as an object with zero Temperature cannot exist in any meaningful manner because it would have no energy, nothing can exist without Consciousness and Joy because without Consciousness it would not know how to be, and without Joy it would not want to be.

We are so used to seeing the world as purely physical, that attributing consciousness and joy to inanimate objects may look like an erroneous anthropomorphic attribution, but it may well be the other way around. To think that only we humans have consciousness and joy, gives us a strange exceptional position in the universe and makes both our own existence and the existence of the universe incomprehensible. The moment physicists realised that gravity must work in the same manner throughout the universe, they could not only better understand the place the earth occupies within the rest of the universe but also develop a better understanding of how gravity works on earth. Similarly, the Vedic assumption that consciousness and joy are universal properties of everything, makes it not only clear how we humans fit into reality as a whole, but also allows us to develop a more realistic and effective understanding of how these two crucial aspects of human existence work in our own daily lives.

We will have a look at those practical applications later. The question we'll try to deal with here is the more theoretical question, how the complex, ever-changing world as we know it could have arisen out of the peaceful, unchanging infinitudes of saccidānanda. The answer will, of course, remain to some extent speculative. Our limited minds can in the end only make an educated guess about such things, and all we have to rely on is how well it hangs together with everything else we know and whether we trust and feel "at home" with the idea. Interestingly, the Indian Rishis were well aware of this ambiguity. The oldest Indian text, the Ṛg Veda, famously ends its description of the creation of the world by saying with a rather modern sounding scepticism, "Only the gods know how it happened, or perhaps even they don't know."

Exclusive concentration as the mechanism behind māyā

In the Indian tradition, right from Vedic times, the force that is held responsible for creation is called māyā, and much of the differences between the various schools of Indian philosophy and yoga centre around the way māyā is understood. In essence, māyā is simply the power of manifestation, but how this power is appreciated changed considerably over time. In later philosophical texts, māyā obtained the meaning of illusion, a power which creates an imaginary world that looks real enough to the ignorant, but that has no true existence in itself. Yoga is then described as the process through which one wakes up out of that illusion into the Truth. In the māyāvādin traditions, this position is taken to its extreme and the entire world is considered as māyā in the sense of an illusion produced by adhyāropa, an inexplicable imposition on the purity and immutability of the silent Absolute.1

Philosophy doesn't quite catch the real spirit of māyā, but it is actually a rather charming idea, and the way it works comes out much better in stories. Here is a romantic classic about Narad and Vishnu. What is māyā [p. 303]

It is important to note that the largely negative meaning of māyā does not yet play a major role in the earliest texts of the Indian tradition. In the Ṛg Veda, māyā is still simply a creative power of the Divine which measures out the worlds in front of itself, and the quality of the created world depends on the consciousness of origin. As a result, there are many kinds of māyā. In some places, the word is used for the true power of manifestation that belongs to the divine Mother herself. In others, it belongs to a lesser light (e.g. RV 5.40).

An image that is commonly used in the Indian tradition to explain Maya is that of seeing a snake where there is only a rope. But as Sri Aurobindo points out, this image illustrates why the world may not be the way we see it, but it doesn't explain how the world came into being in the first place: there is still a rope to be explained. Sri Aurobindo gives a different explanation for how our complex evolutionary world came into being. He compares the main process through which Brahman manifests the world out of itself with the kind of “exclusive concentration” that is part of our ordinary mental consciousness. At our human level, exclusive concentration expresses itself in our ability to concentrate on a limited sub-set of all that we can potentially experience at any given moment. When you read this text, for example, your consciousness is guided along by what you read: things like the chair on which you sit, the room, your programme for tomorrow, the house in which you grew up enter your consciousness the moment this text brings them to your attention. Till then, they were there but you were not aware of them.

At the cosmic level, where in Sri Aurobindo's conception consciousness includes the power of creation, Sri Aurobindo describes exclusive concentration as "a self-limitation by Idea proceeding from an infinite liberty within". He then argues that the manifestation of the world out of saccidānanda could have taken place through a simple combination of only two basic powers that must have been present in the original conscious existence, 1) the ability to split itself into many instances of itself,2 and then 2) the ability to apply, in each of these instances, the power of exclusive concentration (The Life Divine, p. 281).

As we saw, the first of these two is the reason why we, tiny, insignificant creatures that we are, can still in some mysterious way know the Divine: every little thing in this universe is in its deepest essence still a true portion of the Divine.3 The second is the origin of the svabhāva, the true spiritual nature of things and beings, including ourselves. As we saw, exclusive concentration may have given different entities different qualities in roughly the same manner that our ordinary human mind thinks of different things at different times, except that it must have worked on a more solid, existential level, not creating a variety of images in one individual human awareness, but a variety of objectively existing objects within the reality of the Divine. In terms of qualities, one could say that while the absolute conscious being of the Divine is inherently anantaguṇa, of infinite quality, each individual entity comes into being with the specific qualities it has, because exclusive concentration creates for it a different subset of that infinite set of qualities.

The formation of subtle worlds

Pure consciousness doesn't suddenly change into hard physical objects. One should imagine it as a gradual process of ever more precisely delimited sets of properties by which in subsequent stages, subtle worlds are created of increasing solidity. As exclusive concentration produces the different qualities of the entities populating this hierarchy of occult, typal worlds, each entity gradually begins to express its own svabhāva, self-nature.

All this may appear strange to us because we have all undergone such a solidly physicalist education that we tend to look at things the other way around. We see the physical world as the original reality and think of ideas only as abstractions derived from that "really real" physical world. Accordingly, we think of creation primarily as a process of bottom-up construction. But this is not how the world works. It is not only poets and storytellers who create personalities and adventures in thin air. Builders, architects, and industrial designers too, start with an idea, a plan, something that exists only in their consciousness, and then detail that plan out top-down. It begins with a vague initial idea, hardly more than an intention, and it ends, after many intermediate stages, with the kind of technical detail that is required to get something actually constructed bottom-up. While mass production can start only after its design has been fully detailed out, single products and prototypes tend to be made somewhat haphazardly, with the details being worked out gradually, in an interaction of top-down and bottom-up processes. A fascinating example of this can be seen in the way small children learn to draw. They begin with scribbling what look like random lines on the paper, seemingly just for the joy of the colours, or for the "kick" they get out of creating something, anything. And then, suddenly, one day, they recognise a few lines in a corner as "papa" — nobody else sees why, but they do — and in their next drawing they do their level-best to accentuate the "papa-ishness" of the lines in that corner and so, gradually, the first match-stick figure sees the light.

Could it be that the awe-inspiring creation of the cosmos has proceeded in a similar way? Neither by an over-sized human-like being creating in one single gesture a perfect pot out of clay, nor by pure chance, but by a "powerful idea" slowly crystallising in an initially amorphous sea of semi-conscious existence? Could the steps in Darwin's evolution have taken place like this? An element of chance as well as a conscious push and pull in the direction of pre-existing "ideas"? First a lot of trial and error, then, once a species is near-perfect, mass-production with all details fixed in its DNA, yet allowing for occasional minor updates?

It is not just the mystics who believed in the power of self-realising ideas. The hypothesis of a top-down creation through exclusive concentration is in harmony with the idealist philosophy of Plato and most other major philosophers not only in India but also in the pre-modern West. As for the hierarchy of occult planes, the descriptions given in different civilizations are, no doubt, different, but still, they are similar enough to give the impression that the differences simply arose because these different civilizations focused on different aspects of a single, but immensely complex underlying reality.

As mentioned earlier, for this text we have used the Vedic description of this inner reality as formulated by Sri Aurobindo.4 In its most simple form, it consists of three parts. There is an upper, divine hemisphere of saccidānanda, which is transcendent, undifferentiated and unmanifest. There is a lower hemisphere of mind, life and matter, which contains the physical as well as the non-physical things, forces and processes, that together produce the mixed, evolving world we inhabit. And in between these two hemispheres, there is a link-plane which is perfectly divine, like the world above it, and yet differentiated, like the world below it. The Vedic rishis called this link-plane, mahat or maharloka; the Upanishads the vijñānamaya kośa; the Greeks knew it is as something that can, if at all, be known only through the highest type of non-dual knowledge, gnosis; Sri Aurobindo calls it the Supramental. We gave slightly more detailed descriptions and definitions of these various layers in the chapter on the Self and the structure of the personality [p. 154] but here we will focus on how all this came into being, since it is our past that carries carries within it the secret of our future.

Endnotes

1To give one striking example of the traditional entirely negative interpretation of māyā, Swami Sivananda, who was in his time considered by many to have the same spiritual stature as Sri Aurobindo and Sri Ramana Maharshi, quotes in one of his books, and clearly in agreement with it, a recommendation by Adi Shankara to look at everything, good and bad, as no better than “the excrement of a crow”. (Adi Shankara, as quoted by Swami Sivananda, 1983/1998).

2Traditional Vedantins might well object against this description, since the Divine is inalienably One and can, of course, not be split. The problem is due to trying to catch reality which is non-dual in a language, and a consciousness, that are dual. Fortunately — and 'fortunately' is much too small a word — reality is not dual, and we humans can learn how to enjoy a consciousness in which the one and the many are equally, and simultaneously, true.

3This inner identity between the one and the many, might also explain those strange phenomena in physics where particles behave at the same time as if they are numerically one and numerically many.

4As mentioned in the chapter on Learning from the Indian knowledge systems, I do realise that this choice is to some extent just a matter of personal preference, but Sri Aurobindo's description is straightforward, logically coherent, in harmony with my personal experience as far as it reaches, and it adds things to the description of reality by mainstream science that to me look crucial to understanding the world as it actually is, while, as far as I know, it doesn't clash with any of the findings of science.

To receive info on

Indian Psychology and the IPI website,

please enter your name, email, etc.